Literature study is an important first step in this stage of analysing the context parameters of our intervention subject. Through definitions, theories, conceptual frameworks and case studies we were able to interconnect the theoretical background provided to our specific research field, to understand the way a socio-technological system works and what components it consists of.

First, a general discussion on the literature is being presented; a table with individual interpretations of literature concepts by each team member follows next. The same applies for all 4 chapters.

Diving deeper into this notion of a socio-technological system (ST&I) as it is defined by Borras & Elder (2014, pg.11), knowledge as one of its key characteristics become obvious. Socio-technical and innovation systems are “articulated ensembles of social and technical elements which interact with each other in distinct ways, are distinguishable from their environment, have developed specific forms of collective knowledge production, knowledge utilization and innovation, and which are oriented towards specific purposes in society and economy.” Production, adoption, diffusion and use of knowledge and technological artefacts among its social and technical elements govern the function of an ST&I system. A wide approach to the theoretical background was intended in the beginning, but we could not overlook the importance of knowledge for both ST&I systems in general and for our sub-system (“Teach your own”); this relation, however, will become clearer in the following chapters. It is a logical assumption that, when knowledge is not properly produced or distributed, then the system is either malfunctioning or it is not inclining towards innovation.

The main elements and the interaction between them are also an important aspect in describing an ST&I. There is always a social dimension that has to be taken into account, which refers to the actors involved in that system: they can be individuals, organizations, state or non-state actors, all with different interests, skills, routines and knowledge, heterogeneous societal preferences, conflicting expectations and ambiguous experiences. It is these agents’ intentionality to take somehow advantage of a system that brings interaction and can induce or prevent a change in the system (Borras & Elder, 2014, p.12).

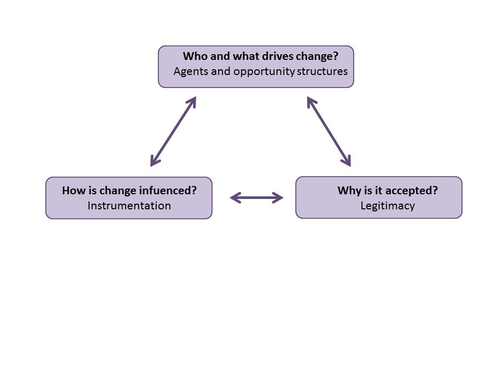

Defining who are these actors, their distribution within a system or their capabilities can lead to thoroughly planning or depicting this change. Surprisingly, a change in the system seems to be driven mostly by societal factors rather than political ones. Besides, what causes an ST&I system to change under pressure, apart from the uncertainty in the production of knowledge and innovation itself, is the change in the societal preferences of its elements. Instrumentation of governance of change, the second pillar for a conceptual framework as described by Borras and Edler (2014), is thus proven crucial for the transformation of a system; who is designing and using the instruments, by whom and how are they shaped, how are they being implemented or even how they interact with each other. Of course, “governance instrument” as a term referring to ways and mechanisms through which agents can induce change, does not only include policy instruments and state agents but also social instruments, i.e. mechanisms for social action by non-state agents (Borras and Edler 2014, pg 31).

Figure 1. Three pillars to understand governance of change in STI systems (Borras & Edler, 2014)

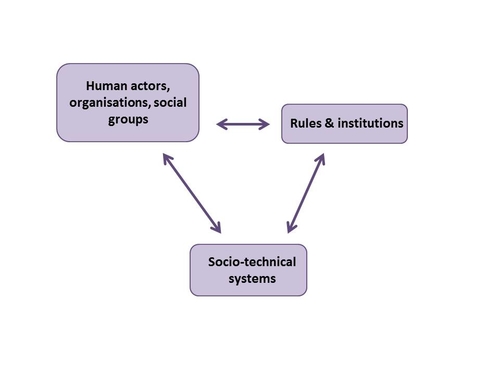

It has therefore become understandable that ST&I systems do not function autonomously but are the outcome of the activities of human actors and the certain characteristics of the social groups. But even these human actors do not act freely; their perceptions are influenced according to Geels (2004, pg.902)by rules and institutions, creating a three interrelated analytic dimension scheme presented below.

Figure 2: Three interrelated analytic dimensions (Geels, 2004)

Due to the variety and the heterogeneity of actor groups within an ST&I system, transformation can either be judged as “good” or “bad”. Happiness and inclusiveness were considered essential for the sustainable transition in the island of Texel during last year’s research, what is also crucial however is for which group of actors was this applicable and to what extent. The different interests of the agents determine the level of acceptance and support for each change. Thus in a sustainability transition process, not only actors that can induce change but also factors opposite to it should be taken into account. Besides, the legitimacy of governing change, as Borras & Edler (2014, pg 35) point out, should enjoy wide social acceptance both of the system and the transformation mechanism itself.

There have been efforts by the literature in order for this transition process to be described and methodologically approached. It can be said that the general steps presented can be proven useful in our analysis as well as in our attempt to envision or predict the sustainability transformation of our system in the future. Pesch (2015, pg 380) likens that process with an S-curve, where four main phases can be observed: the predevelopment stage where there is no visible change in the system, the take-off phase when the transition stages get under way, the acceleration stage where changes are observed in socio-cultural, economic, ecological and institutional levels and finally the stabilization phase where a dynamic equilibrium is reached. The “transition management” is a four-key activities paradigm as well that he uses for the same purpose. There, the organization of the transition arena comes first, meaning the gathering of all actors pursuing a change of the existing regime. Secondly, the development of visions for the new desired situation takes place, followed by the transition experiments stage and the monitoring of the transition process. The third activity seems to be of a bigger importance for our group since it involves processes of social learning and focuses mainly on knowledge distribution within the system. Combined with the last activity, it can give valuable feedback about what extent the transition experiment contribute to social learning.

Last but not least, moving towards a sub-system oriented observation, a closer look into case studies for sustainability transition of islands revealed omissions in their approach. Although the importance of social learning and knowledge production and distribution is highlighted in a big part of the theoretical background as a major pillar for successfully implementing a transition, this was not the case in the examples of Chongming Island and Norfolk Island.

More specifically, in the essay of Huang (2008) the construction of an eco-island, some remarkable statements are made. According to the author, an eco-island is a natural, economical and social complex system and it should consist 6 characteristic details: integrated ecosystem structure and function, powerful ecological security defense system, sustainable use of natural resources, prosperous and stable eco-economy, comfortable human habitats and widespread ecology civilization. As it is pointed out, in order to promote and protect the ecological facilities of the island, ecological awareness, adequate education and training for the total population should be provided by the government and organizations. However, this last part about the key role of education is under lighted in the further research and traditional energy oriented strategies are only to be analytically discussed.

Individual Interpretations

Socio-technical System

|

Team member |

Interpretation |

Comments related to Texel sub-system |

|

Alkistis |

A regime with distinguishable characteristics where social and technological elements interact with each other. Knowledge is being used as a tool towards a specific purpose. |

How knowledge is being distributed is not only important for Texel as a ST system but is also the backbone of the sub-system of “Teach your own”; When knowledge is not properly utilized, then the (sub-)system is either malfunctioning or it is not inclining towards innovation. |

|

Clara |

Technology and people become a whole which defines such a system. It accounts for the interaction of technology with the societal factors in which it is embedded. |

Societal factors (i.e. actors and stakeholders, local culture and environment) are essential for youngsters to stay in the island. 'Teach your own' is much more than ICT. |

|

Menno |

|

|

|

Kimberley |

|

|

Sustainability transition

|

Team member |

Interpretation |

Comments related to Texel sub-system |

|

Alkistis |

A desirable or planned change in the way a ST system works, in order for it to become viable and minimize the environmental impact of the procedures that take place inside it. Transitions steps are made towards a specific goal in the future. |

The goal of the sustainability transition for Texel is already defined (100% sustainable Texel/self-sustained island). For a successful transition in the “teach your own” subsystem, the basic goal has to be formulated as well. |

|

Clara |

A sustainability transition of a socio-technical is a slow change in time towards a situation where technology serves people in a cost-effective way that can be sustained in time. |

The vision proposed for the project is a 'self-sustained Texel by 2065'. The goal of 'Teach your own' needs to support this vision for the whole transition to be succesful: Texel in 2065 will need local people willing to work in local sustainable projects. |

|

Menno |

|

|

|

Kimberley |

|

|

Governance of change

|

Team member |

Interpretation |

Comments related to Texel sub-system |

|

Alkistis |

All instruments, factors, agents that affect (induce or block) change and the way they do it. |

Who is designing and using the governance instruments in Texel, by whom and how are they shaped and how they interact with each other, are aspects needed to be answered in order to lead the transition towards the right direction. |

|

Clara |

Steering of change in a socio-technical system based on inherent dynamics. The three main pillars of governance can be summarized as: who and what drive change, how to do it and how to legitimate it. Governance is not only an state-action (hierarchical mechanism). Market and communication are two other mechanisms for governance of change. |

For 'Teach your own': the two main mechanisms driving change are hierarchy and communication. In order to achieve the subsystem's goal, local people willing to work in the island and educated for it are needed (first pillar). The second pillar is knowledge development, difussion and application. ICT is one instrument for it as well as hands-on activities related to sustainability. We will need to work on the third pillar and how to legitimate 'Teach your own' among the Texelaars. |

|

Menno |

|

|

|

Kimberley |

|

|

Socio-technical niche

|

Team member |

Interpretation |

Comments related to Texel sub-system |

|

Alkistis |

A relatively small and controlled space where ideas, innovation and technologies can be applied and tested. Changes happen faster and results can be more easily observed. |

Sub-systems can be seen as niches for bringing sustainability transitions on the entire island. Texel can be seen as niche for bringing transition in more parts of the world. |

|

Clara |

Protected space for innovation, where new ideas are proven feasible without the economical barriers set by incumbent markets. If a niche is proven succesful, the next step is to prove it marketable and finally lead to a regime shift. A socio-technical niche is useful to observe the relations between people and technology and assess customers' acceptance of a new idea. |

We can see the early stages of 'Texel 2065' as a socio-technical niche: best practices can become marketable -and transferrable to other islands or communities- to achieve a self-sustained system in 2065 . For that, we need to find actors who are willing to 'protect' the ideas of our subsystem at an early stage |

|

Menno |

|

|

|

Kimberley |

|

|