1.3 Future Socio Technological System

Since Texel is an island it is an ideal niche situation to start from. The strange thing though at this moment is that part of the waste regeneration is done outside the island. Since this is merely solving the problem, but moving the problem (literally in this case), this will not set an example to the rest of the world and is not something that could be taken over on a larger scale by the mainland.

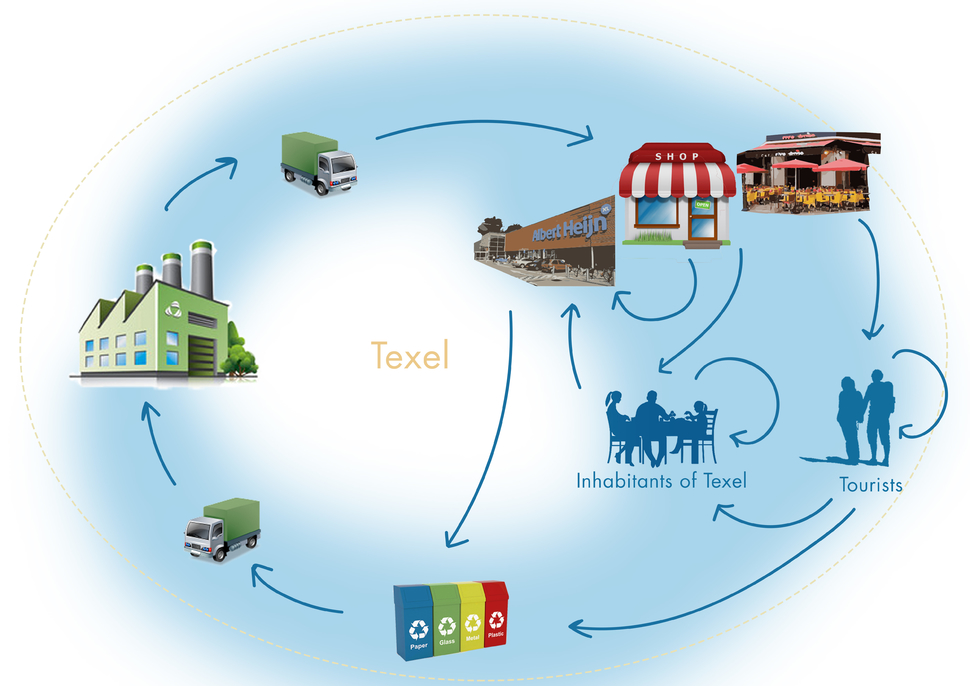

To be able to set a proper example as a community the approach has to include the complete socio technological system. The goal is to create a closed loop at Texel; meaning all the resources used for new products will be coming from the island itself and the ‘waste’ generated during use or end of life will be brought back to something useful for Texel, striving for loss in products in general (nothing leaving the loop).

This could be done by:

- recycling the waste

This is a difficult option since energy and other resources are needed to be able to recycle materials. Since it is depended on the kind of materials it will be an option that is not left out of the system. Important is that the materials are separated. This could be done either at the source (people doing it themselves) or collectively (at the recycling plant by the use of technologies). - Reuse; for reuse there are a couple of different options

- Adding a function to the product after use. In this way the lifespan of a product will be increased. There is still an end of life scenario though, which still has to be taken into account.

- Second hand store. This option is only possible if the products are still intact, this requires a good durability.

- Salvation of parts. This is a good option if there are vulnerable and less vulnerable parts at a product for example. Reusing the less vulnerable parts will decrease the amount of waste in total.

- Landfill on the island; This seems like a really unsustainable option, but it could be something to look into. Burning waste is not necessarily an unsustainable way of waste treatment. Biowaste for example could be used to create biofuel. Within the same line of burning, the ashes that are created when burning plastics for example can be used to produce asfalt.

What does this scenario exactly take into account and how would this future scenario look like?

In the table below the technologies, actors and regulations of the future scenario are shown.

|

Technologies |

Actors |

Regulations |

|

Separation of materials for full recycling |

Tourists |

Payment for collecting waste |

|

Recognition of different materials |

leisure industry |

stimulation of handing in used products ( |

|

collection of waste |

agricultural sector |

entrance regulations of island in general |

|

transportation of transport |

inhabitors of Texel |

|

|

communication tools to instruct people about system (especially tourists) |

Companies based on Texel |

|

|

Waste treatment companies |

||

|

government of Texel |

The Technologies

The technologies involved include the transportation of the waste. This could be done by car for example, but there could also be a situation where the transportation is not needed at all, since the reuse will happen on a very small surface. Other technologies involved include technologies to enable reuse or recycling of materials.

The Actors

An important Actor within this system is the tourist sector. The reason that Texel has to deal with a large amount of waste is because of the great amount of tourists using the facilities during the summer. Not only do the tourists themselves bring a lot of waste to the island. There is also the fact that the waste of a lot of leisure facilities (like restaurants) is not collected properly (see chapter 1.2 for more information). Including these facilities in the project will help creating a big impact already from the start.

The Regulations

Regulations for the future scenario mostly have to do with the stimulation of gathering materials and the way of collecting and transporting the waste when it is offered. The regulations will be an extra stimulation for the mind changing that has to happen. Apart from stimulation it is also important that there is room for initiatives when it comes to reusing or recycling. At this moment, for example, it is not possible to use recycled plastics in the food industry because of regulations, even if it is proven to be clean, the risk is not taken.

References

- Geels,F.W.,2002,Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study, Research Policy 31, pp. 1257-1274.

- Hughes, T.P., 1987. The evolution of large technological systems.In: Bijker, W.E., Hughes, T.P., Pinch, T. (Eds.), The Social Construction of Technological Systems: New Directions in the Sociology and History of Technology. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 51–82.

- Borrás, S., & Edler, J. (2014). Introduction: on governance, systems and change. In S. Borras & J. Edler (Eds.), The governance of socio-technical systems (pp. 1-2; 11-16; 23-xx). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- J. Markard, B. Truffer, (2008),Technological innovation systems and the multi-level perspective: Towards an integrated framework, Research Policy, 37 (2008) 596-615.

- Van Eijck J., Romijn H. (2008) Prospects for Jatropha biofuels in Tanzania: An analysis with Strategic Niche Management, Energy Policy 36: 311-325.

- Pesch, U. (2015). Tracing discursive space: Agency and change in sustainability transitions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 90: 379-388

- A. Smith, J.-P. Voß, J. Grin, (2010), Innovation studies and sustainability transitions: the allure of the multi-level perspective and its challenges, Res. Policy 39 (2010) 435–448.

- Huang, K. G. and F. E. Murray, (2010), ‘Entrepreneurial experiments in science policy: Analyzing the Human Genome Project’, Research Policy, 39 (5),567–582.

- Rip, A., T. J. Misa and J. Schot, (1995), Managing Technology in Society: The

Approach of Constructive Technology Assessment, London: Pinter.

- Bowman, D. M. and G. A. Hodge (2009), ‘Counting on codes: An examination of transnational codes as a regulatory governance mechanism for nanotechnologies’,Regulation and Governance, 2 (3), 145–164.

- Webb, K. (2004), ‘Understanding the voluntary Codes phenomenon’, in K. Webb

- (ed.), Voluntary Codes: Private Governance, the Public Interest and Innovation,Ottawa: Carleton University, Carleton Research Unit for Innovation, Science and Environment, pp. 3–32.

- Easton, D. (1965), A Systems Analysis of Political Life, New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Miller, S. (2001), ‘Public understanding of science at the crossroads’, Public

Understanding of Science, 10 (1), 115–120.

- Hagendijk, R. and A. Irwin (2006), ‘Public deliberation and governance: Engaging with science and technology in contemporary Europe’, Minerva, 44 (2), 167–184.

- CBS. (2014). Statline: Municipal waste; quantities. Visited on November 15, 2015, from Centraal bureau voor de statistiek: http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLEN&PA=7467eng&D1=90-91,95,106,140,143-147&D2=0&D3=19-21&LA=EN&HDR=T&STB=G1,G2&VW=T

- CBS. (2014). Statline: Huishoudelijk afval per gemeente per inwoner. Visited on November 15, 2015, from Centraal bureau voor de statistiek: http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=80563ned&D1=a&D2=439&D3=a&HDR=T&STB=G1,G2&VW=T

- Gemeente Texel. (2013). Grondstoffenplan. Retrieved from Gemeente Texel - Beleidsstukken: http://www.texel.nl/de-gemeente/beleidsstukken_42781/item/grondstoffenplan_40903.html

- Green Islands Network. (2015). Netherlands: Texel. Visited on November 15, 2015, from Globalislands.net: http://www.globalislands.net/greenislands/index.php?region=8&c=27