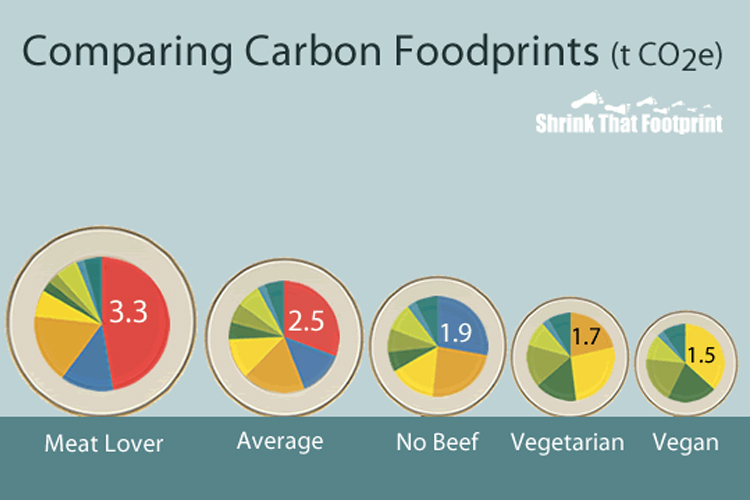

Following on last week’s column and the climate negotiations in Paris I was wondering how much our food really is contributing to climate change. Last week I found out that agriculture is a major driver of climate change. Globally, food systems are responsible for about thirty percent of all human driven greenhouse gas emissions and the production of animals and of crops for feed alone accounts for nearly a third of global deforestation. From food (and drink) system related products meat turns out to be an important negative factor; global emissions are generated for 15% by the livestock sector. Because of this big role my column will focus on the effects of meat and the reduction of meat consumption.

Reducing meat consumption could be critical to keep global warming below the critical mark of two degrees Celsius. To make the size of the problem, or potential solution, more tangible; the earlier mentioned 15% of yearly emissions produced by the livestock sector is comparable to the yearly amount of exhaust emissions of all the vehicles used in the world. And that is not all, according to research performed by Chatham house the consumption of meat even is expected to increase with 76 percent by 2050. This increase is mainly caused by a so called ‘protein transition’ that is currently happening across the developing world: as incomes rise, consumption of meat increases. A growing global population cannot converge on developed-country levels of meat consumption without huge social and environmental cost. In the developed world, although extremely high, per capita the demand for meat has reached a stable level. These extremely high levels of meat consumption in industrialized countries are on average twice, and for the United States almost three times, as much as experts estimate being healthy. Overconsumption in general, but of animal products and processed meat in particular, is already contributing to the rise and growing problem of obesity and non-communicable diseases like cancer, heart diseases and type-2 diabetes.

As countries prepared a new international deal at the UN climate change conference in Paris, a gap remains between the emission reductions countries have proposed and what is required for a decent chance of keeping temperature rise below 2°C (and preferably even 1,5 degrees Celsius). Governments are in need of credible strategies to close this gap, and reducing meat consumption could be one of them: according to the previous mentioned research worldwide adoption of a healthy diet would generate over a quarter of the emission reductions needed by 2050.

So, there is a compelling case for a shift in diets, and especially for addressing global meat consumption. However, governments are caught in a cycle of inertia: they fear the consequences of possible intervention, while low public awareness between livestock, diet and climate change means they feel no real pressure to intervene.

The Chatham house report states that action is needed on three fronts:

Build the case for government intervention. To help mobilize policy-makers a compelling evidence base that resonates with existing policy objectives such as managing healthcare costs, reducing emissions and implementing international frameworks could be used.Needed: evaluation of the economic grounds for change; alignment with the broader sustainability agenda; establishment of international norms for a sustainable, healthy diet; building the evidence base for policy-makers; working across governments.

Initiate national debates about meat consumption. Increased public awareness about the problems of and caused by overconsumption of animal products could help to disrupt the cycle of inertia, thereby creating better domestic circumstances and the political space for policy intervention. This role should be taken by governments, the media, the scientific community, civil society and responsible business. Needed: tailored strategies to national contexts; a broad message that is focussing on the co-benefits of reduced consumption; an accessible and simple message that focusses on hard-hitting facts and visual linkages between meat, dairy products and climate change; the mobilization of mainstream media, this signals importance; engagement of independent and surprising communicators. Non-partisan experts will be most trusted by publics and should be central to any awareness-raising campaigns.

Pursue comprehensive approaches. Shifting diets requires comprehensive strategies, which together will have more effect than the sum of their parts by sending a powerful message to consumers that the reduction of meat consumption is beneficial and that the government takes the issue seriously. Needed: expanded choice and amount of alternatives; capitalizing on public procurement to reach a larger section of the population and to demonstrate commitment to the issue; use of price to promote alternatives; learning by doing, strategies should be tested; support for innovation; promotion and protection of diversity.

By now, the government should see the need to revisit assumptions that reducing meat consumption is too difficult or too risky. As the global burden of food related diseases grows, policies aimed at reducing the intake of salt, sugar and unhealthy fats are proliferating. The capacity of governments to influence diets is expanding and people increasingly accept the role of government in this area. In my opinion including meat consumption in such efforts would both help deliver on the public health agenda and also meeting environmental objectives.