In the literature, technological transitions are explained using a variety of theoretical frameworks. In this section, three of the most commonly used frameworks will be briefly discussed: the multilevel perspective, strategic niche management and transition management.

The multilevel perspective

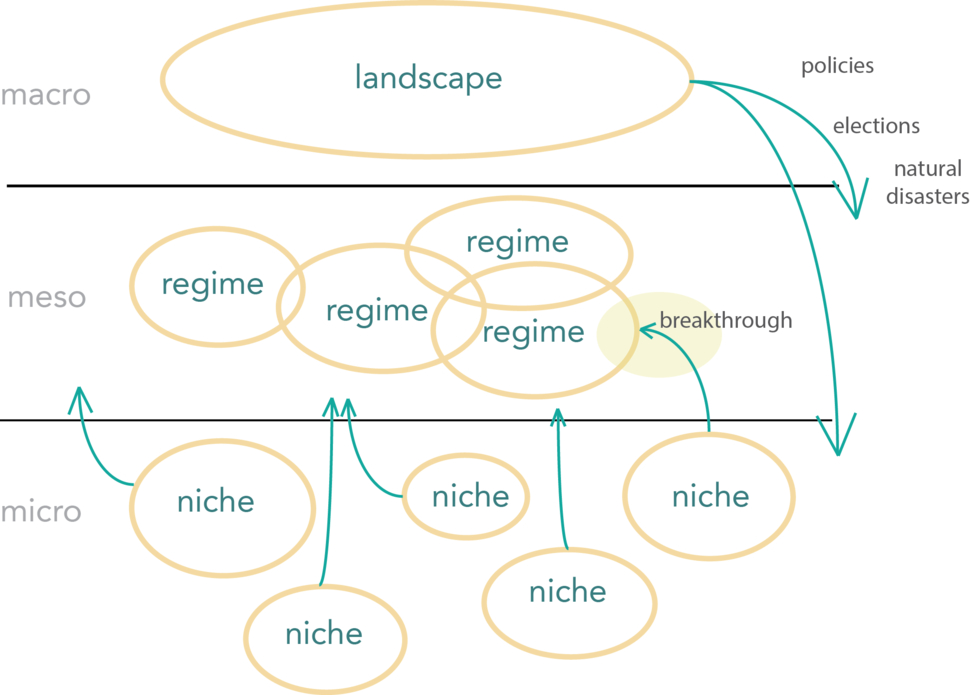

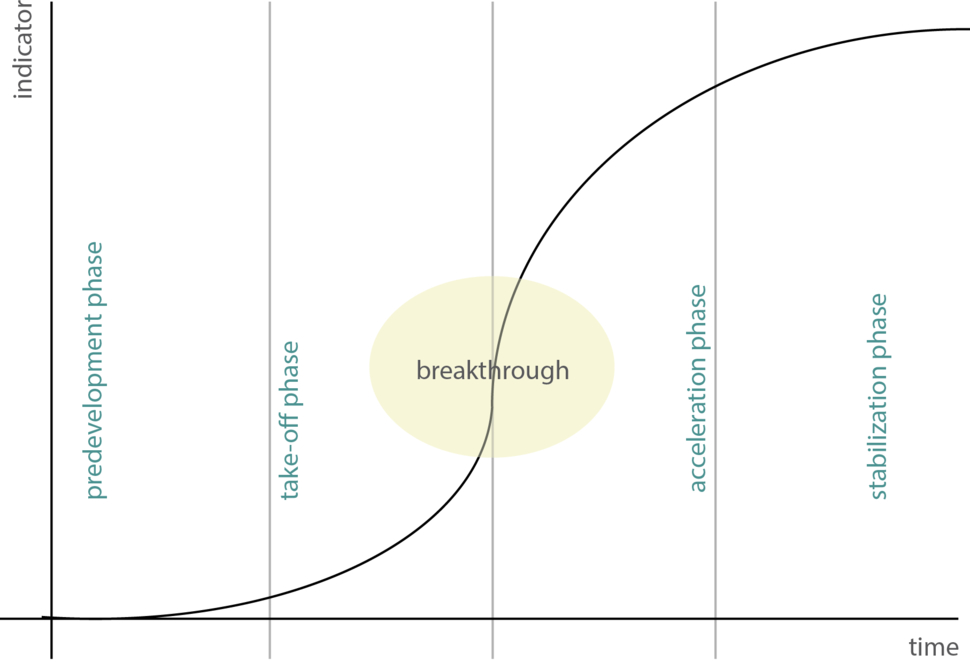

The multilevel perspective (MLP) (Geels, 2002) describes a socio-technical system as a three-layered system, where each layer influences the other both directly and indirectly. These three levels are: landscape, regime and niche (figure 1.3).

The outcomes of the landscape level, however, have a considerable impact on the transformation dynamics within regimes, which are part of the the next level (suitably named the regime level). The term “regimes” originates from Nelson and Winter (1982) and can be described as a patchwork of varying actors who share common organisational and cognitive routines, leading more or less to a common technological trajectory. In addition, Geels (2002, p.1259) states that “Technological regimes result in technological trajectories, because the community of engineers searches in the same direction. Technological regimes create stability because they guide the innovative activity towards incremental improvements along trajectories.” It is important to note that technological trajectories are not only influenced by engineers, but also by users, policy makers, societal groups, suppliers, scientists, capital banks and so forth.

The final level is called the “niche” layer. Niches are generally ‘protected spaces’ such as research & development (R&D) laboratories, subsidized demonstration projects, or small parts of the market where users have special demands and are willing to support emerging innovations. Initially, the (often technological) novelties that are developed in this market are generally unstable and present low technology performance. However, they are thought to provide the seeds for systemic change, and as such are crucial for transitions to happen (Geels, 2011).

strategic niche management

Logically, the MLP’s niche level is where strategic niche management (SNM) comes into view. SNM can in short be explained by a well-articulated definition by Kemp et al. (1998, p.186) who defines strategic management as follows:

“Strategic niche management is the creation, development and controlled phase-out of protected spaces for the development and use of promising technologies by means of experimentation, with the aim of (1) learning about the desirability of the new technology and (2) enhancing the further development and the rate of application of the new technology."

Kemp et al., (1998) also identify several strategies that are used to reach the goals within this definition, namely

- The articulation (and adjustment) of expectations or visions of actors in the network, which provide guidance to the innovation activities.

- The building of social networks and the enrolment of more actors, which expand the resources of niche-innovations.

- Learning and articulation processes on various dimensions, e.g. technical design, market demand and user preferences, infrastructure requirements, organizational issues and business models, policy instruments and symbolic meanings.

transition management

group interpretation on literature

|

Group member |

Literature interpretation |

Application to Texel / general comments |

|

Jeffrey |

Interesting literature on transition and system description. Most important is to be aware of the interrelation between technology and social factors. Technology itself is not sufficient, it is important to know how to manage it too in order to break through existing regimes and become influential. Most importantly to boost sustainability. |

Most of this literature seems to be focussing on technology transitions. I’m not sure how to translate this to entrepreneurs as a system. However, the multilevel perspective could be an interesting base for the description of our entrepreneur sub-system. |

|

Karolina |

Borrás & Adler (2014): In order to be able to design an overarching strategy, the systems must be thoroughly examined and understood with regard to different types of agents fostering or preventing change as well as instruments and legitimacy (a concept of governance of change). Pesch (2015): Niches may be the stimulus of the sustainability transition; however through the formulation of the conceptual framework (role of agency), this article tries to go even beyond the niche. |

The three pillars of ST systems may guide us through while coming up with the subsystem of entrepreneurial; especially in notion who is the change driver (whether the entrepreneur as supply side or the customer as demand side) and why sustainability could be accepted by the customers. The problem of scaling up niches (entrepreneurial business) to the level of regime is noted and as such is very important in regard to sustainability. If a business wants to be sustainable, thus have social and environmental impact, it needs to be able to be scaled up not only size-wise. but also in regard to changing markets and contexts |

|

Robert |

Borrás & Adler (2014): I believe we have all experienced the big why questions when thinking about sustaining our lifestyles. Why is it so hard if we know it is essential? The answers are tried to be given in this paper by mapping the who, how and why pillars. Discussing all available literature enables them to carefully bridge a gap and show the importance of analytical and empirical efforts in thoroughly studying socio-technological governance in general. A possible change in this is even a step further and shows many uncertainties on the way. The paper is a first step in mapping this socio-technological change. Pesch (2015): In my opinion, the paper tries to address the problem that transitions can’t be initiated until the structure of present systems and the actors within that system is clear. As a possible answer, it describes several system representations and adds possible transitions in that system. |

For our system in Texel, I believe the mapping of the system, including actors and eventually transition strategies within that system are essential for our objective. The representation of the Texel market of sustainable entrepreneurship and using niches to break current regimes could be very interesting to establish a transition over 50 years.

|

reflection on the literature

In order to create a sustainable, self-sufficient Texel in 2065 a lot of change is needed. To identify the desired changes and how to potentially reach them, it is important to map out Texel as a system. Because we work with several groups of students, this system can be divided in sub-systems for greater depth.

System change can result in various ways. For instance, new niche innovations can become successful enough to break into an incumbent regime, bringing about change with the regime. However, change can also come from within the regimes, though less radically than through niches. This can be through new R&D for existing technologies, for example. In any case, we believe that entrepreneurs are important actors that can drive change, most importantly through innovative ideas and start-ups.