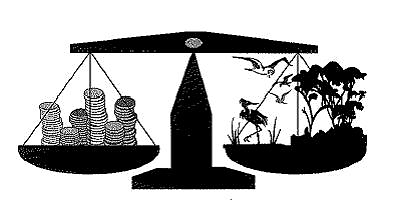

As Renes & Romijn (2014) explained in their article, a Societal Cost-Benefit Analysis (SCBA) offers an overview of the impacts and effects of policy measures, their hazards and uncertainties and the quantified advantages and disadvantages, usually quantified in money (euros for example). This monetarization of benefits and risks leads to the equation ‘benefits minus risks’ and hereby we have calculated the effect of the policy measure on the societal prosperity. Positive means good, negative means bad. SCBA’s are very useful when large projects, e.g. the construction of critical infrastructures, are being developed. Performing this analysis maps all the possible effects of the infrastructure on the environment and thus creates a better understanding of the consequences of the projects’ implementation. Because of its objective weighting of impacts and interests, SCBA as defense of policy remains uncontested. Communication between stakeholders can be enhanced by using SCBA’s, highlighting which parties and groups will be affected by the project. Also the involvement and weighing of broad public values in this analysis, taking the dynamic character of these values into account, makes SCBA a widely accepted ex ante tool for possibly risky projects. Right?

Figure 1. Example of a (simple) Societal Cost-Benefit Analysis

Well, it’s quite different. Although SCBA’s are being supported by the Dutch government and many policymakers [1], still there’s a lot to say about them. Niek Mouter, my former teacher, has done research on using SCBA’s in practice and he concluded that, next to pros, there are several cons on this analysis (Mouter, 2012). I’ll summarize a few of them:

- Outcomes of SCBA’s are uncertain and contested because of the many assumptions that have to be done with regard to future economic and demographic development

- Not every impact or effect can be quantified or monetarized

- Limitations of SCBA’s can be used strategically by policymakers to say ‘no’ to policy; also, parties can hide themselves behind the SCBA so that they don’t have to say ‘no’ themselves

- As a result of the previous con, the objective value of SCBA’s will lose power

Aad Correlje, also my former teacher, mentioned in his lecture that formal evaluation methods like SCBA’s offer opportunities for public participation and objections, leading to preconditions and operational requirements [2]. However, the gap between those formal evaluation methods and the informal (public) considerations is growing. SCBA’s seem not capable of involving the dynamic public values at the right moment, resulting in social uprisings and clashes. Because of this, SCBA’s can become counterproductive in infrastructure planning. How can SCBA clear its name again?

Recently, I’ve done research on the governance of windfarms in the Netherlands and SCBA’s form a big part of the planning of these farms. Nowadays these ‘Euromasten’ are experienced as great hindrance by the local population. What I thus propose is a ‘governance of SCBA’s’ in order to improve transparency and value embeddedness. Should we want to price the priceless? What if human lives have to be valued? How much is ours worth and who decides this? And what if risks to human beings are strategically being underestimated by self-interested policy makers? This could lead to dangerous situations!

Figure 2. Local population protesting against windmills

SCBA needs a serious Responsible Metamorphosis. Back-room decisions? No, from beginning till end, the local population, being affected by the infrastructure project, has to be involved. No black swans, but a cooperative attitude is key. In order to reduce the growing discrepancy between formal policymakers and the informal public, the methodology and presentation of SCBA’s have to be designed value-sensitive and, more important, have to be 100% transparent. I’ve learned with the Responsible Innovation Minor that value and interest conflicts not automatically lead to bad things. No, these conflicts are opportunities to innovate the analysis as a whole and embed values within it, so that SCBA connects business with the informal. The challenge is to design policy (i.e. construction of infrastructure) such that risks for the local population are minimized while societal prosperity is maximized. Transform SCBA into a societal project in which the local people can fully participate. Only then, this analysis can provide an overview of all the risks being taken and be interpreted meaningfully. After all, it stays a Societal Cost-Benefit Analysis.

Sources

Mouter, N. (2012). Voordelen en nadelen van de Maatschappelijke Kosten-en Baten analyse nader uitgewerkt. In Colloquium Vervoersplanologisch Speurwerk 2012, Amsterdam, 22-23 november 2012. Stichting Colloquium Vervoersplanologisch Speurwerk (CVS).

Renes, G., Romijn, G. (2014), Een algemene leidraad voor maatschappelijke kosten-batenanalyse. In ESB, Dossier MKBA: maatwerk in gebruik, Jaargang 99 (4696S), 23 oktober 2014, 6-11.