Ever since I first encountered the term “Responsible Innovation”, about 7 weeks ago now, there has been one thought that popped into my head particularly often: “What a tiresome business this is sometimes.” To really be a Responsible Innovator, you have to take into account so many things. So many what ifs, dilemmas (morally overloaded or not), value conflicts, problems of many hands, risks, uncertainties… And the most fascinating of all: the unknown unknowns. Things you didn’t know you didn’t know. Even if you took every little thing into account, thought about every tiny risk, there’s always that: the surprises.

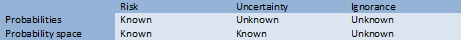

Just to make clear what is meant exactly by unknown unknowns in the context of RI, take a look at the following table:

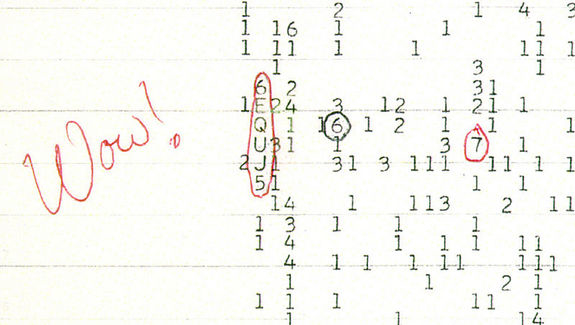

If a decision is made under risk, it means that we know what the possible outcomes of the decision are (the so-called probability space), and with what probabilities these outcomes occur. Therefore, risks can be called the known knowns. If we face a decision under uncertainty, the possible outcomes are known, but we cannot assign meaningful probabilities to these outcomes. These are then called known unknowns: the things we know we don’t know. And then there is ignorance. This is basically the situation where we have no idea at all: we don’t know what the outcomes of a certain decision may be and we know even less about their probabilities. To give an example in this last category: Space. We still have no idea what planets outside the Milky way look like. There is no evidence that there is intelligent life out there. But there’s also no evidence that there isn’t. And if there is, will it be friendly? Will it look like us? Should we try to reach it, make contact with it? Or have they already discovered us long ago? Space is full of unknown unknowns.

It was in 2002 that United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld made the term “unknown unknowns” famous, when he used it during a Pentagon news briefing. It was during the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and a year before the invasion of Iraq, that a reporter asked Rumsfeld if there was any evidence that Iraq was supplying terrorists with weapons of mass destruction. And then, this happened:

Presumably, the argument Rumsfeld intended to use was “just because we can’t find any evidence that Saddam Hussein has weapons of mass destruction, doesn’t mean he doesn’t have them”. You can imagine that this comment raised quite some laughter and controversy, but Rumsfeld does have a point here. As he wrote in his appropriately titled book “Known and Unknown: A Memoir”:

“The information that those in positions of responsibility have access to, is almost always incomplete. […] It is difficult to accept – to know – that there may be important unknowns.”

The more I think about this, the more I agree with it. But this shouldn’t be seen as a problem, but rather as an opportunity. Because isn’t this the exact fact that makes us explore the world around us? That made Columbus sail across the sea, discovering something that he could never have imagined: another continent? That makes us shoot rockets into space, just to find out what’s out there? Making the unknown known is an intrinsic force that drives humans to discover, to innovate. Even if we have no idea what might happen to us, we are willing to take the risk, simply because we cannot accept the unknown to stay unknown. So let me come back to my previous statement that RI is a tiresome business. It might actually be one of the most exciting ones.

Curious about this Rumsfeld fellow? Read this series of brilliant essays for the New York Times by writer and filmmaker Errol Morris, called “The Certainty of Donald Rumsfeld”. Morris also made a documentary about Rumsfeld, called “The Unknown Known”.

Image: In 1977, this signal (now called the Wow!-signal) was detected from space by a strong narrowband radio. Evidence that there is life out there?